Back Stitching...a short story

The past year was one in which I wrote a fair amount, mostly short fiction, some poetry. These days it's hard to imagine continuing that discipline the way I did...the time squeeze I've allowed myself to fall into has really taken me away from a few things that I really really enjoy, most notably writing and some regular physical outlet like tennis, golf, weightlifting...

All that being said, I feel Spring working on me. A good sign... as a friend likes to say, a good sight better than pushing up daisies.

So I'll give Spring a nod by posting a short, short story written last year. It is fiction, but folks close to me may be tempted to think otherwise. They (you) should resist that inclination...insofar as the ways in which they (you) would be wrong would be more significant probably than the ways in which they (you) might be right.

I've only barely shopped this story around, with no success, so it seems this blog might be a good place for it live for awhile... enough prologue.

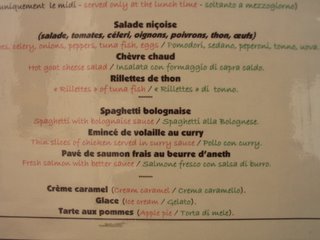

note: click on image for a larger view.

Back Stitching

a short story

by Kevin Cahill

It begins with a rending. A million different circumstances can masquerade as the cause, but really they are all of two kinds. One is born of violence, the other of fatigue. A sharp knife-like edge bears in from the outside directed by chance or by intent. It tears into the flesh or fabric of life and leaves a gaping wound. Or. A movement so familiar, so often repeated, that it barely registers any longer as a conscious act and then suddenly the shockingly mundane failure to cohere, to hold together…but again the gaping wound. Were it not for such openings, nothing would find its way into the world.

Out of such a wound I came. No more children. That’s what the doctor told my mother after the death of my twin brother. It was a long time before I began to appreciate how much work I had to do. To repair what I had done by merely being born. To stitch back together what I had torn. Looking back I sometimes feel as though I was engaged in that work long before I became aware even of the wound. Even as a toddler it was as if I were being artfully wielded like a needle and thread by some cosmic seamstress to backstitch together the lips of that wound, that it might close again without complaint and with hardly a trace. Later, in my age of reason and discernment, I perceived that Life had become threadbare from so much wearing, from all the personal strivings, the marriages, the jobs, the adventures, and the children. It was, I think, the children, our children, my children that prompted the flood of memories, long forgotten. Strange to see them enacted again this time before my eyes. As if I were my own father. As if time’s arrow were really a blanket, folded on itself. Enfolding me in it.

So I undertook to imitate Her handiwork. I took up needle and thread and thimble and began the quiet and methodical work of stitching together the rent folds, the gaping lips. I learned the necessity of piercing that which is serviceable for the sake of that which has lost its utility, of drawing a slender alien thread forward and backward through the tissues of time and thus restoring a million disparate moments into the same warp and woof of life, all of them joined in a mystery of… simultaneity. Yes.

When I was 19 I finally committed to paper a memory that had, it seemed to me, become as permanent a fixture in my mind as the painting on the wall of our living room, the one say of a drawing of the Virgin tacked to a corn stalk in a cornfield along a lonely road in Oaxaca. Beth only just noticed it as we careened around a corner in our old VW. Backing up, we saw it, saw her, part avatar of fertility, part scarecrow, a highway accident waiting to happen. We snapped her from the car window. And now she hangs on the wall of our living room...more real than I remember her.

Just like my childhood memory. It came effortlessly and in perfect detail. A young boy of five exploring the entrails of a ramshackle chicken house at the most distant part of his parents’ lot. The chicken house has been converted to storage for old furniture and the like. Inside the dark and twisted labyrinth the boy loses track of where he is and then scrambles out through an opening in the floor. He crawls a few paces, scuttling under unfamiliar brush and suddenly finds himself on a green lawn. A few feet away he sees a small pond and beside it a boy his own age on his bare knees peering into the water. He gets up and goes to the pond. He kneels beside the boy who seems not to notice him. When he looks down at the pond he sees an enormous gold fish, floating languidly in the still water. The two boys remain thus for a few seconds, and then they see each other’s reflections and smile. My memory ended there, framed on either end by blank space. It was the happiest moment of my boyhood.

I’m reading a magazine on the couch. Tess, my four year old daughter, walks past me. As she does she declares matter-of-factly. “If I die, you have to get a new girl.” She continue past me on her way to her bedroom. I look up at her and can think of nothing to say except, “Alright.” I consider adding something like, “But she won’t be the same girl, not the same as you.” Or. “Why would you die, sweetie?” Instead I stand pat with, “Alright.” Tess looks back at me from the door. She seems satisfied that I have listened. I offer my hand, hoping to draw her to me so that I can hold her, but she wheels and enters her room. Alone again I look at the magazine as if it is a treasure map. I wonder where lay the wellsprings of her words?

Two weeks later I am telling Tess a bedtime story. Colm, who is two, lies nearby in his bed and eavesdrops. It is tale of unicorns, Starlight and Sparkledust, and their half brother Seth. There are dragons, painful separations, tokens of magic, adventures and reunions. It is a long, rambling serial tale that has occupied the better part of a winter season. This night we have begun to recount the previous episode’s ending when our new cat Jasper jumps up on the bed. Tess breaks away from the story to grab Jasper and pull him over to her side. He is a big docile tomcat who seems tolerant of just about any kind of manhandling. Perfect for the kids. About a month ago a friend had offered Jasper to us. She was simplifying her life, getting down from nine pets to one or two. Jasper was a good match, she thought. She was right. He purrs and kneads the comforter. Tess strokes his fur carefully. I lie back and bide my time. I think about tonight’s episode. What crisis will I invent that will send Tess sliding under her sheets in fear, and what surprise will bring her out and remind her of the world’s goodness?

The next morning I wake up. Beside me, between me and my wife, Colm lies asleep on his back, his arm slung out across my chest. Sometime in the night, in the dark, he made the journey alone to this spot. Something is heavy on my feet. It’s Jasper. Gently I nudge him off the edge of the bed. I hear him land on the carpet. It’s strange to have a pet again. Our last pet was an exuberant, knuckleheaded chocolate lab Chesapeake mix named Muddy. We shipped Muddy off to some friends in the country a year ago after the second time she inadvertently knocked Colm down a flight of stairs. It so happened that our other pet, a cat named Zephyr, passed away about a month later. We buried Zephyr in the back yard under one our apple trees. Later that summer we would also bury there, Pesca, the children’s first goldfish. As I lay still half asleep in my bed next to my wife, these facts and impressions paraded rather lazily through my mind when my daughter’s words appeared again. “If I die, you have to get a new girl.” I saw in an instant the ground under the apple tree from which those words had sprouted. I marveled at the length of time they had gestated there, dormant for six seasons until they had burst forth in all their starkly arresting truth. Eighteen long months, nearly half her life, had been stitched together into a synaptic and luminous moment. Then her lips parted as if she were some oracle. It had taken me two weeks to grasp its startling symmetry. Jasper and Zephyr. Life and Death. Tess and a Father’s desire to have his little girl forever.

A few minutes later Tess comes into the room in her underwear, her hair disheveled. She climbs wordlessly into bed next to Beth who has quietly lifted up the blanket to let her in. I can feel the languor settling over all four of us. It is as palpable and as luxurious as a down comforter. Soon we are all going to be asleep together here in the same bed. Even as I drift off, I wonder if I am the last one. I wonder what future incident is already stitched to this moment and being drawn tight, and by what thread, by what hand? Where, I wonder, is Jasper?

When I showed what I had written to my parents they both smiled. Even though I was in college, it seemed very much like a reenactment of me bringing home work from fifth grade. They each read it together. My father reading over my mother’s shoulder, both of them reading slowly so as not to turn pages before the other was finished. They remembered the chicken house. “What a nice story.” said my mother.

I corrected her. “It’s not a story. It really happened. I remember it.” I can see from my mother’s eyes that she has already decided not to say something so I say, “Who was he?”

“Who?”

“The boy behind our house. Who was he?”

“There was no boy on our street,” she said.

“Nor a pond,” my father added.

It was unthinkable to me in that moment that my most companionable memory was a fiction. Part of me privately decided that my mother was lying to me.

The goldfish buried beneath the apple tree in our back yard was named Pesca. He only lived a couple of days. When I was a kid my goldfish was killed when my younger sister poured red KoolAid into the fish bowl. That’s not how Pesca died. I came into the kitchen to find both Tess and Colm gently stroking Pesca’s side as he lay mouth gaping open in the palm of her hand. We put him back in the bowl but he was probably dead before he hit the water. We never got another fish after Pesca. Part of me didn’t want to bury the memory of one fish beneath the remains of so many subsequent others. Not to mention the one that had come decades before.

It's Spring and I'm lying in the hammock in the backyard. Colm is only three months old. The fine hairs on his head tickle my chin as I look up through the pruned branches of our gnarled apple trees. Since we lived in Mexico years ago I've become partial to hammocks. In our previous house we also had one under an apple tree. That tree, though just as old as the one I'm under now, was never pruned. It was a home for birds. It's unruly branches extended far beyond the reach of any ladder. In autumn you had to watch your head; the fruit came down from high above. But in spring it made a dazzling white mottled canopy of blossoms against the blue sky. I remember one day lying there with my guitar on my chest. My eyes were closed. I was close to dozing. I felt a puff of breeze on my cheek and then the faintest tone of the fat E string...I could have easily mistaken the sound for a memory or a pure imagining, but when I opened my eyes I saw a single white blossom lying across the strings. Colm breathes silently, his little chest expanding and contracting in turns. Against the blue sky I see the dark, backlit rough bark of the tree. Sprouting incongruously from this aging and tenacious thing are delicate white blossoms.

Some day perhaps Colm will tell a story about a fish he once had. Perhaps his story will resemble the one I just told you, but experience tells me that I may well not recognize it. I may not have the presence of mind at that age to connect the dots. It’s funny. People say things without realizing they might as well be broadcasting grass seed. Like the doctor who never could have imagined a younger sisiter whose birth would not kill my mother but whose life would ultimately kill my gold fish. Like my daughter whose affection for a cat and intimations of mortality pierce my heart this morning. Like me and my tales of dragons and a little boy whose reflection in the still waters of that fish laden pond must have looked more like me than I did to my own mother.

For awhile, a good long while in fact, it seemed like I couldn’t help but watch Life rush past, draining out of the hole I had left behind me. But lately, I feel a pull. It’s as if I’m being drawn up. Not out of this world exactly, but drawn up next to something, closer.